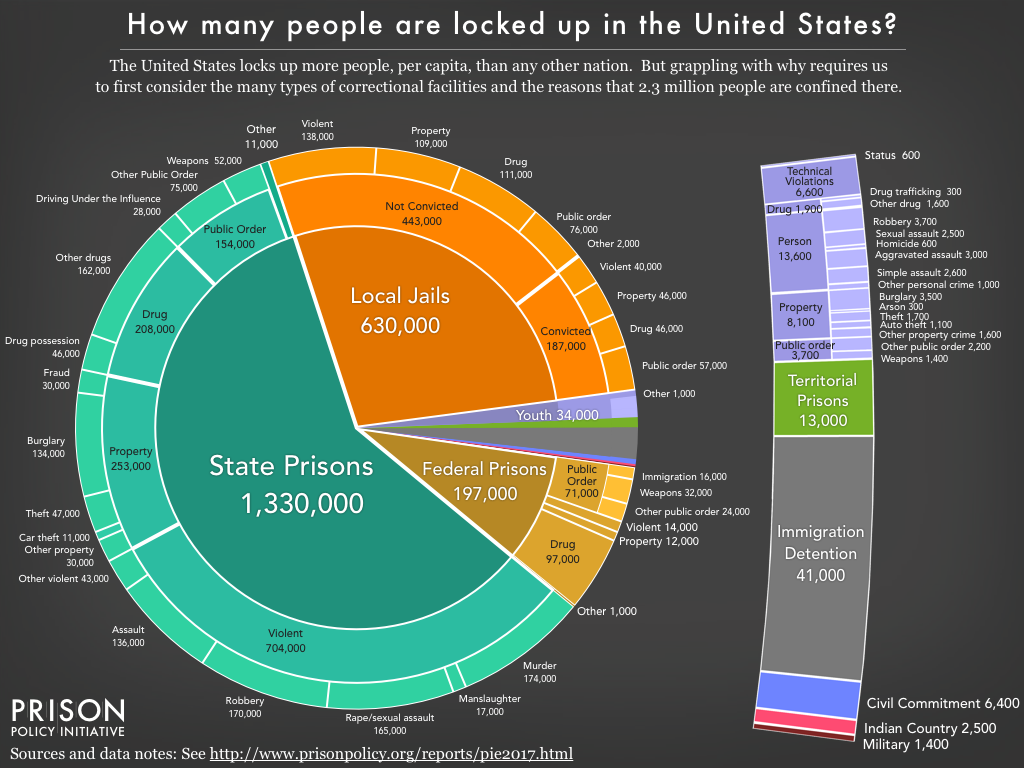

The Prison Policy Initiative creates a yearly pie chart that details the makeup of the U.S. prison system. In 2017, 2.3 million U.S. citizens were imprisoned in 5,961 facilities nationwide, ranging from Indian Country Jails to Federal and State prisons. About a quarter were imprisoned for nonviolent drug crimes (including 7,200 youth), and 16,000 for nonviolent immigration charges.

Following their incarceration, a staggering portion of these inmates will then get caught in “jail churn,” officially known as recidivism. Many of those released from the prison system come right back.

Being confined with other criminals for years at a time creates psychological damage and social stunting. So, although there are education, early release, and job training programs in place in prisons, the system continues to expand. There’s been a 500% increase in the last 40 years, according to The Sentencing Project.

One Answer is Green

Countless problems need addressing throughout the system, but one approach that can help is to make prisons more green. Although the United States is the global leader in incarceration, the prison system also offers real opportunity for betterment.

Going green can help prevent “jail churn” in two important ways:

(1) Mental Environment: Universities from the University of Minnesota to Stanford, as well as organizations like GreenPeace, have carried out studies showing the linkage between human well being and nature. It’s clear that daily exposure to the natural environment reduces symptoms of anxiety, stress and even depression. In correctional facilities, one of the most “violent and stressful environments,” it’s especially needed.

This is particularly true for inmates held in solitary confinement. Statistics show that the more than 80,000 inmates each year who spend time in solitary confinement are more likely to commit violent crimes during the jail churn.

At the Snake River Correctional Facility in Oregon, a study concluded that even providing nature films to the inmate population in solitary confinement provides far better psychological outcomes for them. The practice earned the prison a Time Magazine award for “One of the 25 Best Inventions of 2014.”

(2) Job Prospects for Released Inmates: Howard Husock, vice president for policy research at the Manhattan Institute for Policy Research, notes,“If people get drawn back into the real world, get a job and make a living, studies show they’ll be less likely to go back to prison.”

Environmental training programs can play a major role in reducing jail churn, transforming both the prison system and the communities most affected by the system.

A prime example is the San Quentin’s Insight Prison Garden Program. San Quentin partners with Planting Justice to provide master gardener training to inmates while they’re incarcerated, as well as to offer job placement after release. The training qualifies the formerly-incarcerated individuals for $17/hour jobs that not only increase opportunities for them upon release, but also reduces food deserts and creates more appealing and productive green space, replacing lawns with gardens.

Plus, the necessary steps for going green are in place, with resources like CorrectionsOne (an online corrections resource) and templates for success like Sustainability in Prisons Project. The National Institute of Justice also provides guidelines to follow and programs to benchmark against.

Green Prisons Also Make Financial Sense

As the U.S. prison system expands, it’s also becoming more expensive. As Eve Tahmincioglu, an award-winning labor and career columnist for msnbc.com, states: “The cost of housing, feeding and providing medical care for America’s prison population has surged over the past two decades, from $11 billion a year to more than $50 billion.”

Again, going green can help.

In CorrectionsOne’s blog post 7 steps to save $1,000 per inmate by “going green,” author Paul Sheldon describes how more efficient lighting, HVAC units, plug-in appliances, motors and pumps, and water/waste systems, can save a correctional facility an average of $1,000 per inmate. Sheldon explains that there’s an abundance of third-party financiers willing to front the cost and be repaid by sharing in the savings that result from implementing these “low-hanging fruit” sustainability initiatives.

Robust standards and frameworks offer guidance for correctional facilities wishing to adopt such changes:

- Greening Corrections Technology Guidebook, National Institute of Justice

- National Institute of Corrections’ Greening Corrections Manual

- Audit Standard and Policy on Sustainability-Oriented and Environmentally Responsible Practices in Corrections, American Correctional Association

Prisons can also turn to numerous success stories of green correctional transformations that have saved tax payer dollars and contributed to greater sustainability.

We will likely always have prisons, but greening them has the potential to slow their growth and reduce their impact–most importantly on their inmates, but also on the environment and on the tax payer.