Recently I sat down with Alexandro Segade to discuss the inspiration and creative process behind his speculative, multimedia theater epic Future St. which will be part of WE’RE WATCHING this April. Segade is an interdisciplinary artist whose work in performance, video, and multi-media installation uses genres, and the theories associated with them, to foreground the politics and myths of representation. Segade is a founding member of the collective My Barbarian, with Malik Gaines and Jade Gordon. Segade and Gaines have also collaborated on performance projects including a recently debut of a choral opera based on an unpublished novel by science fiction author Octavia Butler. Segade is co- chair of the Film/Video department at Bard College’s Milton Avery Graduate School of Arts and teaches in the BFA program at Parsons in New York City. Segade was born in San Diego, CA, and lives and works in New York and Los Angeles.

Recently I sat down with Alexandro Segade to discuss the inspiration and creative process behind his speculative, multimedia theater epic Future St. which will be part of WE’RE WATCHING this April. Segade is an interdisciplinary artist whose work in performance, video, and multi-media installation uses genres, and the theories associated with them, to foreground the politics and myths of representation. Segade is a founding member of the collective My Barbarian, with Malik Gaines and Jade Gordon. Segade and Gaines have also collaborated on performance projects including a recently debut of a choral opera based on an unpublished novel by science fiction author Octavia Butler. Segade is co- chair of the Film/Video department at Bard College’s Milton Avery Graduate School of Arts and teaches in the BFA program at Parsons in New York City. Segade was born in San Diego, CA, and lives and works in New York and Los Angeles.

Anna Gallagher-Ross: Since November, and even prior to that time, we’ve been watching this dystopian discourse unfold in the political arena, which at times can feel like a sci-fi saga.

Alexandro Segade: Absolutely.

AGR: In light of that, could you talk about what sparked Future Street?

AS: It’s interesting that right after the election, people started to talk about how 1984 had become a bestseller again. In all my work, I have attempted to address both the concerns of the moment and the historical and artistic precedents for the moment.

AGR: Right.

AS: And during this moment, and leading up to it, other dystopian novels and films were being looked at as models for understanding what was happening and what was to come, from Parable of the Sower to The Handmaid’s Tale. My piece, Future St, which describes a utopia for some, and dystopia for the rest, talks about a lot of the issues we contend with right now: autocracy, spectacle, performances of masculinity, feminism and queerness, technology, and surveillance. The piece grew very slowly out of my MFA thesis at UCLA, where I was making work about the debate around gay marriage. It was 2008, California had voted for Proposition 8, which banned gay marriage in the state. There was a window when gay marriage was legal and my partner Malik Gaines and I got married, knowing that our marriage was going to be contested. The feeling I had at that moment was one of a kind: on the one hand there was the election of Obama, and a promise that democracy could function, but on the other hand, we had everybody voting against our personal relationship. I was also interested in the debate within queer communities: not everybody thought “marriage equality” was a great idea. It normalizes relationships, forecloses possibilities, is a marker of privilege, and institutionalizes intimacy.

AGR: What was your perspective on this debate?

AS: Ultimately, Malik and I were ambivalent about marriage, but we needed healthcare, and we wanted to be able to visit each other if we ended up in the hospital. I started to make performances in order to understand these contradictions: writing speeches and conversations, having performers rehearse them, resulting in installations and videos, but I hadn’t found a form. Finally, I found my solution in genre itself: tropes that offer us both a space of possibility and a structure that can be resisted. Science fiction was the perfect way to go because I was thinking so much about what societies could be. The idea was to take all of these anxieties about this marriage debate and ask: what would happen if a society were built to affirm my identity, rather than destroy it? I started writing about a future homosexual police state, affirming fears on all sides of the gay marriage debate. I imagined a society based on cloning, with clones who were mandated to marry each other, who were also cops, just sitting in a cop car talking about their relationship and the society that they were sworn to protect. And from there a whole world started to get built.

AGR: You produced a series of performances on this subject, right?

AS: Yes. The first one was called Replicant v. Separatist, which was about the clone cops policing the younger generation who didn’t like the idea of gay marriage and were rebelling against the sexual identity mandated by the clones. Then that developed into another piece called Other Boys and Other Stories which focused more on this generational dissonance. The third performance, Holo Library, is where surveillance began to play a role. I wanted to explore how sexuality and identity have become part of a media landscape that involves screens, sexting, the ways people communicate without a physical body-to-body relationship. In L.A., a lot of gay bars were closing and a big reason was apps like Grindr and SCRUFF. I was thinking about what it means when we start to meditate sexuality, when our relationship is with a screen, rather than a person. I started imagining: what if the screens had consciousness and they were actually aware of their function as conduits? And after Holo Library there was a project called Boy Band Audition which was the least scripted. In it, I would pretend to be the future, and that I was putting together a boy band from the present in order to change the timeline with a hit single. It was a really funny piece.

Future St. brings all these threads together into one one evening length piece. I’ve brought together a team of artists that I really admire. Casting has been an adventure because I’m from L.A. and most of the performers that I’ve worked with on this project are in California. It is really important to me that the actors have a stake in the material so I’ve been going to an LGBTQ-supportive acting studio in New York City. I’m working with actors who identify as gay, trans, and gender queer. I didn’t want this performance to be a bunch of cis male muscle guys wandering around onstage pretending it’s the future…to me that would be really scary.

AGR: Absolutely. Could you say a bit more about the dystopian science fiction models that Future St. draws upon?

AS: I’m a huge fan of science fiction. Ursula Le Guin, Samuel R Delany, and Octavia Butler are three of my favorite writers of all time. I also really like HP Lovecraft. There are also certain filmic examples like Blade Runner, which was one of the first movies I saw in the theater and I remember forgetting I even existed. I just lived in it, was completely seduced by the aesthetic and the mise-en-scéne. As an X-Men comics fan, I love melancholy and existentialism.

AGR: Not to nerd out, but your plot of clones and rebels also makes me think of early Batman, which features the mutant rebellion, who eventually become the sons of Batman…What is so fascinating is you are playing with these science fiction tropes, which in many ways in can be quite normative, and you are inserting this queer, feminist politics…

AS: Completely. As I got older I realized some of the flaws of Blade Runner, such as its unrelenting male gaze. I thought a lot about that image of the woman on a screen that floats above the city in that film. I play with that image in Future St. Why is there a woman on the screen? Is that an interface that could be masking a consciousness of some kind? In Future St. there is this group of older women who are called the Mother’s Brigade, who precede the clone culture and represent the generation of feminists that includes the artist Mary Kelly, who was my mentor at UCLA, and also, of course, my own mother, Irina Kaplan-Segade, who is an activist with GLSEN. What is easily overlooked in the kinds of debates that we have right now is that a lot of the tools for understanding what’s happening can be found in older models of critique and liberation. Feminism is an important touchstone here. I don’t know how we could have an understanding of gender, or more broadly, humanity, without feminist critique.

AGR: Could you talk a bit about the relationship between spectacle and surveillance in Future St.?

AS: That’s an interesting question. We often talk about spectacle in relation to Guy Debord’s The Society of the Spectacle. Debord understood that we were becoming a society mediated through images, and it is the case now that everyone’s relationships are mediated through images. The Situationist critique was that we aren’t living our full lives and therefore we need some kind of participatory situation. But one thing that wasn’t technologically possible for the Situationists was the possibility of direct participation in that spectacle. Eventually we became the content providers for the spectacle through that participation, and the content we provide can be and is surveilled.

In developing this imaginary gay autocratic state, I’ve been doing research on the connections between fringe homosexual politics and Fascism. We have all of these different permutations, from the Nazi Ernst Rohm, to gay skinheads like Nicky Crane, slain Dutch politician Pim Fortuyn, tech tycoon Peter Thiel, and I-don’t-know-what-you-would-call-him Milo Yiannopoulos, who is finally in trouble for making statements that seem to support pedophilia, I guess. Yiannopoulos used various subcultural outlets, such as 4Chan and Breitbart, to communicate with his audience, but when re-contextualized his statements became evidence that could be used against him. Privacy no longer exists as such, and surveillance becomes a frame for the data we produce—willingly or not. People don’t always pay attention to it until it’s time to pay attention to it, but the information is out there.

This is a large part of Future St. The main character finds himself in trouble because everything that he’s ever done has been tracked, and the Replicant police have collected a script about his life, including his memories, and it is their interpretation of that script that determines his fate. In the current moment, when I am on Facebook, I have the sense of surveilling myself and of self-censorship. I put tape over the camera on my laptop, and I keep reading about people’s cell phones being searched at borders. Paranoia is normalized. We are living inside of a spectacle that leads to surveillance automatically: it’s a loop.

AGR: I agree. When I first read about Future St., it seemed fantastic, but also all too real.

AS: I think that’s something that we’ve been thinking about as we work on the text and the design. We keep asking ourselves: is this science fiction? That’s the thing with speculative fiction: it is always this commentary on the current the moment. It feels like it’s futuristic but really it is about the time we are living in.

To find out more and to purchase tickets click here.

traditional narratives and established performer-audience relationships have been opened up to create possibilities of innovative discovery. Big Art Group blends high and low technology, marginal and mainstream culture, and blunt investigation to drive questions about contemporary experience. Manson and Nelson also created the social network and website

traditional narratives and established performer-audience relationships have been opened up to create possibilities of innovative discovery. Big Art Group blends high and low technology, marginal and mainstream culture, and blunt investigation to drive questions about contemporary experience. Manson and Nelson also created the social network and website

Annie Dorsen works across the fields of theater, film, dance, and digital performance. Between 2010 and 2015, she created a trilogy of algorithmic performances: Hello Hi There, A Piece of Work, and Yesterday Tomorrow. She is a 2017 recipient of the Foundation for Contemporary Arts Theater/Performance award, and a 2014 recipient of the Herb Alpert Award in the Arts. She has taught at Bard College, New York University, Fordham University, and the University of Chicago.

Annie Dorsen works across the fields of theater, film, dance, and digital performance. Between 2010 and 2015, she created a trilogy of algorithmic performances: Hello Hi There, A Piece of Work, and Yesterday Tomorrow. She is a 2017 recipient of the Foundation for Contemporary Arts Theater/Performance award, and a 2014 recipient of the Herb Alpert Award in the Arts. She has taught at Bard College, New York University, Fordham University, and the University of Chicago.

Recently I sat down with Alexandro Segade to discuss the inspiration and creative process behind his speculative, multimedia theater epic Future St. which will be part of WE’RE WATCHING this April. Segade is an interdisciplinary artist whose work in performance, video, and multi-media installation uses genres, and the theories associated with them, to foreground the politics and myths of representation. Segade is a founding member of the collective My Barbarian, with Malik Gaines and Jade Gordon. Segade and Gaines have also collaborated on performance projects including a recently debut of a choral opera based on an unpublished novel by science fiction author Octavia Butler. Segade is co- chair of the Film/Video department at Bard College’s Milton Avery Graduate School of Arts and teaches in the BFA program at Parsons in New York City. Segade was born in San Diego, CA, and lives and works in New York and Los Angeles.

Recently I sat down with Alexandro Segade to discuss the inspiration and creative process behind his speculative, multimedia theater epic Future St. which will be part of WE’RE WATCHING this April. Segade is an interdisciplinary artist whose work in performance, video, and multi-media installation uses genres, and the theories associated with them, to foreground the politics and myths of representation. Segade is a founding member of the collective My Barbarian, with Malik Gaines and Jade Gordon. Segade and Gaines have also collaborated on performance projects including a recently debut of a choral opera based on an unpublished novel by science fiction author Octavia Butler. Segade is co- chair of the Film/Video department at Bard College’s Milton Avery Graduate School of Arts and teaches in the BFA program at Parsons in New York City. Segade was born in San Diego, CA, and lives and works in New York and Los Angeles.

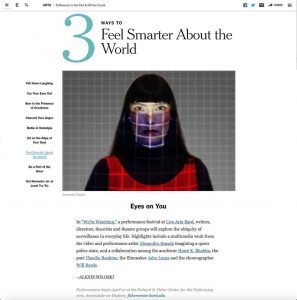

This past January team members of What Remains were in residence at The Fisher Center for Performing Arts. Premiering at WE’RE WATCHING this April, What Remains is a collaboration between poet, essayist, playwright, and editor, Claudia Rankine, author of the acclaimed poetry collection, Citizen: An American Lyric, among other important works; documentary photographer and filmmaker John Lucas, who has directed and produced several cutting-edge multimedia projects including a collaborative series of video essays with Rankine entitled “Situations”; and artist and writer, Will Rawls, who works with dance, objects, sound and speech in solo and group performances that explore the idea of self and becoming. This interview was conducted at the beginning of the creative process for What Remains.

This past January team members of What Remains were in residence at The Fisher Center for Performing Arts. Premiering at WE’RE WATCHING this April, What Remains is a collaboration between poet, essayist, playwright, and editor, Claudia Rankine, author of the acclaimed poetry collection, Citizen: An American Lyric, among other important works; documentary photographer and filmmaker John Lucas, who has directed and produced several cutting-edge multimedia projects including a collaborative series of video essays with Rankine entitled “Situations”; and artist and writer, Will Rawls, who works with dance, objects, sound and speech in solo and group performances that explore the idea of self and becoming. This interview was conducted at the beginning of the creative process for What Remains.