Michael Stephens | October 26, 2011

Today in the New Yorker John Cassidy asks “where is the new Keynes”? Where, in other words, are the new ideas that have emerged from this historic economic crisis? While there is nothing, he insists, comparable to a new Keynesianism, there has been a rediscovery of some “important ideas.” The first:

1. Finance matters. This lesson might seem obvious to the man in the street, but many economists somehow managed to forget it. Two who didn’t were Hyman Minsky and Wynne Godley, both of who were associated with the Levy Institute for Economics at Bard College. Minksy’s now-famous “Financial Instability Hypothesis” can be found here, and one of Godley’s warnings about excessive household debt can be found here. (It is from 1999!)

Comments

Michael Stephens | October 25, 2011

Research Associates Marshall Auerback and Rob Parenteau have a long piece up at Naked Capitalism taking on the lazy anthropology that poses as economic analysis regarding Greece and the euro zone crisis. With respect to the image of Greeks lolling about living off an absurdly generous dole at the expense of frugal Germans, they provide some helpful contextual data:

… the Greek social safety nets might seem very generous by US standards but are truly modest compared to the rest of the Europe. On average, for 1998-2007 Greece spent only €3530.47 per capita on social protection benefits… By contrast, Germany and France spent more than double the Greek level, while the original Eurozone 12 level averaged €6251.78. Even Ireland, which has one of the most neoliberal economies in the euro area, spent more on social protection than the supposedly profligate Greeks.

One would think that if the Greek welfare system was as generous and inefficient as it is usually described, then administrative costs would be higher than that of more disciplined governments such as the German and French. But this is obviously not the case, as Professors Dimitri Papadimitriou, Randy Wray and Yeva Nersisyan illustrate. Even spending on pensions, which is the main target of the neoliberals, is lower than in other European countries.

Comments

Michael Stephens |

Here’s one fairly standard reading of our economic policy challenge: the economy needs more pump priming, the federal government has more than enough fiscal space to provide it, but for political reasons it won’t be forthcoming. (If you needed further evidence of that last proposition, take a look at the latest House Republican job creation offering: repealing a law designed to prevent tax evasion by federal contractors, paid for by kicking some seniors off of Medicaid. Take a moment to gape at the boundary-probing cynicism. This is the legislative equivalent of planting a giant foam middle finger on the White House lawn.) So as far as aggregate demand goes, in other words, there’s little reason to think that the federal government will step into the breach (and as things stand, we expect the government to be withdrawing demand from this economy). But a new one-pager by Pavlina Tcherneva (“Beyond Pump Priming“) suggests that the above reading of the situation is … too optimistic.

Even if the AJA, or some other form of aggregate demand injection is passed, there are serious limitations to relying too heavily on an approach that boils down to boosting growth and hoping for the right employment side effects. Featuring a rather stark graph portraying the ratcheting up of long-term unemployment over the last several decades, the piece argues that there are shortcomings to relying too exclusively on pump priming (which is largely what the AJA is, aside from a small amount of infrastructure).

The alternative is to take dead aim at the employment outcomes we need—to directly target the unemployed. Tcherneva explains why, instead of just trying to fill the demand gap for output, we ought to focus on closing the demand gap for labor, through public works and job guarantee programs that directly employ the unemployed. Among the benefits of the latter approach are an ability to focus on particularly distressed regions of the country.

Read the one-pager here.

Comments

Michael Stephens | October 24, 2011

“You cannot solve the problem with this level of financing. It’s not possible.”

Dimitri Papadimitriou, interviewed yesterday for Ian Masters’ “Background Briefing,” gets to the heart of the matter on the shortcomings of the proposals for resolving the eurozone crisis that are currently on the table. Papadimitriou argues that we’re likely looking at a default from the Greek state and that estimates of bondholders facing a 50-60 percent haircut are actually quite optimistic. He also discusses the possibilities of the “contagion” spreading to this side of the pond. Listen to the full interview here.

Comments

Michael Stephens |

The office of Senator Bernie Sanders (Independent – Vermont) has announced the formation of a panel tasked with drafting legislation to reform the Federal Reserve. Levy Senior Scholars Randall Wray and James Galbraith and Research Associate Stephanie Kelton have been named to the team.

Wray’s recent brief on the Federal Reserve, co-authored with Scott Fullwiler (“It’s Time to Rein in the Fed“), looks at our over-reliance on the Fed (something Wray has discussed elsewhere) and the relative lack of transparency and oversight, wading into issues surrounding democratic accountability and the “independence” of the central bank:

There is no difference between a Treasury guarantee of a private liability and a Fed guarantee. If the Fed buys an asset (say, a mortgage-backed security) by “crediting a balance sheet,” it is no different from the Treasury buying an asset by “crediting a balance sheet.” The impact on Uncle Sam’s balance sheet is the same in either case: it is the creation, in dollars, of government liabilities, and it leaves the government holding some asset that could carry default risk.

…in practice, the Fed’s promises are ultimately Uncle Sam’s promises, and they are made without the approval of Congress—and in some cases, even without its knowing about them months after the fact. [We are not] implying that Uncle Sam would be unable to keep such promises. There is no default risk on federal government debt, and the government can afford to meet any and all commitments it makes. Rather, we are simply emphasizing that a Fed promise is ultimately a Treasury promise that carries the full faith and credit of the United States. Our question is one of accountability: should the Fed be able to make these commitments behind closed doors, without the consent of Congress?

Read the policy brief here (one-pager here).

An earlier working paper by Galbraith et al created quite a bit of buzz for its data suggesting the presence of partisan bias in Fed policy during presidential election years (an issue that came up again quite recently), but its main arguments centered around identifying the “real” reaction function of the Fed: namely, that in recent decades the central motivating force behind Fed behavior is a fear of full employment. The paper also reveals that Fed policy plays a significant role in increasing inequality. Read the working paper here. (Galbraith’s 2009 congressional testimony on the Fed is here.)

Comments

Thomas Masterson | October 21, 2011

I study the distribution of wealth and income here at the Levy Institute, so I read the first five hundred words of Robert Samuelson’s Washington Post column on inequality (“The backlash against the rich,” Oct. 9th) with interest and approval. But I knew it couldn’t last. Once Samuelson gets beyond description and attempts explanation and analysis, he is clearly out of his depth.

Samuelson turns his gaze to the proposal to raise income taxes on those with incomes above a million dollars, whom he refers to as “job creators”—a Republican Party talking point that Samuelson repeats uncritically. He makes two mistakes in citing a paper, written by my colleague Ed Wolff, in which the distribution of assets for the top 1% of households by wealth (total assets minus total debt) is compared to the distribution for the bottom 80%. First, Samuelson seems to assume that those people who own privately held businesses are small business owners. Second, not all of the people in the top 1% of household wealth are households making more than $1 million a year in income.

In Ed Wolff’s paper we see that the wealthiest 1% of U.S. households in 2007 held more than half of their net worth in “unincorporated business equity and other real estate,” and only 26% in financial assets such as stocks, mutual funds, bonds, etc. It is clear that Samuelson is translating the former category as “small and medium-sized companies.” This could be an honest mistake. But it is a mistake. There is no evidence in Ed Wolff’s paper that the top 1% contains all (or no) “small business owners.” Just that they hold twice as much wealth in privately held businesses as in publicly traded businesses. And as Kevin Drum of Mother Jones put it, “[w]e’re talking about people who earn upwards of a million dollars a year, after all. You don’t get that from taking a minority stake in your brother-in-law’s auto shop.”

If we actually look at those U.S. households receiving $1 million or more in income (using the 2007 Survey of Consumer Finances, as Ed Wolff does), we are talking about 0.37% of households. In terms of the composition of their assets, the picture is pretty much the same for them as for the wealthiest 1% of U.S. households. But only 24% of the top 1% of household wealth are in the million-dollar income club. If you look at the bottom 99.6% or the bottom 80%, the picture is very different. continue reading…

Comments

Michael Stephens | October 20, 2011

Are you a reclusive economist-savant who happens to know how a member state might be able to exit the European Monetary Union in an orderly fashion? Would your idea appeal to a center-right British think tank? If so, you need to shave your beard and put in for the Wolfson Prize (don’t worry, with the 250,000 pounds sterling you can buy a new beard). Via Free Exchange, the winning proposal will be chosen by a panel of economists selected by Policy Exchange, a London-based think tank. Lord Wolfson of Aspley Guise, who is putting up the cash, explains what they’re looking for: “Consideration will need to be given to what a post-euro Eurozone would look like, how transition could be achieved and how the interests of employment, savers, and debtors would be balanced. Importantly, careful consideration must also be given to managing the potential impact on the international banking system.”

Some of the Levy Institute’s work on the eurozone crisis more generally can be found here:

Comments

L. Randall Wray | October 19, 2011

(cross posted at EconoMonitor)

Government Sachs posted its second quarterly loss since it went public in 1999. No doubt that has sent Washington scrambling to try to plug the leak. (Wouldn’t it be fun to listen in on Timothy Geithner’s incoming phone calls from 200 West Street, NYC, today?)

Lloyd “doing God’s work” Blankfein blamed the “uncertain macroeconomic and market conditions”—conditions created, of course, by Wall Street. And since Wall Street refuses to let Washington do anything to improve those conditions, expect much more hemorrhaging among Wall Street’s finest.

The big banks are toast, as I’ve been saying for quite some time. There is no plausible path to real profits with the economy tanking. Only jobs—millions and millions of them, as well as comprehensive debt relief will stop that.

As I wrote a couple of weeks ago:

“US and European banks probably are already insolvent. When Greece defaults and the crisis spreads to the periphery that will become more obvious. The smaller US banks are in trouble because of the economic crisis. However, the biggest banks that caused the crisis are still reeling from their mistakes during the run-up to the crisis. They were already insolvent when the GFC hit, and are still insolvent. Policy makers have pursued an “extend and pretend” approach to hide the insolvencies, however, the sorry state of these banks will be exposed when the next crisis begins to spread. It is looking increasingly likely that the opening salvo will come from Europe, although it is certainly possible that it could come … The economy is tanking. Real estate prices are not recovering, indeed, they continue to fall on trend. Few jobs are being created. Defaults and delinquencies are not improving. GDP growth is falling. Household debt as a percent of GDP is only down from 100% to 90%. While declining debt ratios are good, it is still too much to service. Consumer debt fell from $12.5 trillion in 2008 to $11.4 trillion now. Total US debt is about five times GDP and while household borrowing has gone negative, debt loads remain high. Financial institutions are still heavily indebted—mostly to one another. At the level of the economy as a whole, it is still a massive Ponzi scheme—that will collapse sooner or later… No real economic recovery can begin without job growth in the neighborhood of 300,000 new jobs per month and no one is predicting that for years to come.

Isn’t it strange that Wall Street has managed to remain largely unaffected? continue reading…

Comments

Michael Stephens |

Pavlina Tcherneva was interviewed recently on Wisconsin Public Radio’s “At Issue” with Ben Merens and took questions from listeners. She argues that while there are plenty of good job creation ideas available, it is ultimately the toxic political environment that is holding us back. Beginning at the 33:54 mark, responding to a question about payroll taxes, Tcherneva pounces on the idea that the federal deficit should be a policy priority: “in and of itself, the deficit should not be a policy objective.”

Download the interview here (begins at the 2:20 mark).

Comments

Greg Hannsgen | October 18, 2011

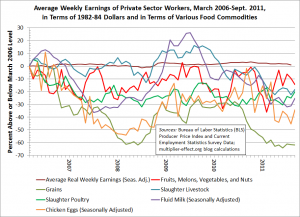

(Click to enlarge.)

(Click to enlarge.)

Signs of serious inflation in broad price indices such as the consumer price index (CPI) have been rare over the past few years, confounding many critics of the stimulus bill and the Fed’s efforts to reduce interest rates. However, as I reported in a blog entry last spring, most food-commodity prices were rising at that time and had reached levels rivaling those last seen in 2008, when unusually severe food shortages caused serious problems in many parts of the world.

The figure at the top of this post is an update of the graph in the earlier post, based on data released this morning by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). The brown line shows the government’s estimate of the average real weekly wage for U.S. private sector employees. The series is of course adjusted for overall inflation, so that it represents actual purchasing power, not a number of dollars. (I have used a slightly different wage series than I used last time.)

The other lines show the same weekly earnings data series in terms of various categories of wholesale agricultural commodities, rather than a varied “shopping cart” of retail goods and services. Each line represents the value of average weekly earnings in terms of one major “food group,” to slightly misuse terminology from the federal government’s old dietary guidelines. For example, the data shown by the red line indicate that a worker measuring his or her weekly pay in an equivalent amount of fruits, melons, vegetables, and nuts would find that his or her weekly pay fell by 14.3 percent between March 2006 and last month. continue reading…

Comments

ShareThis

ShareThis