Michael Stephens | November 3, 2011

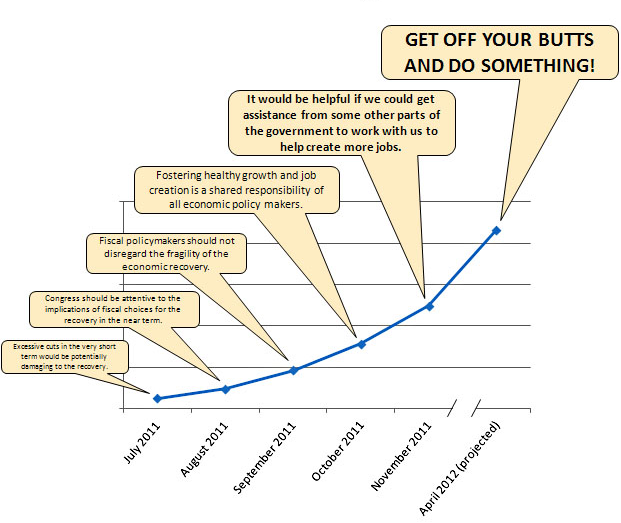

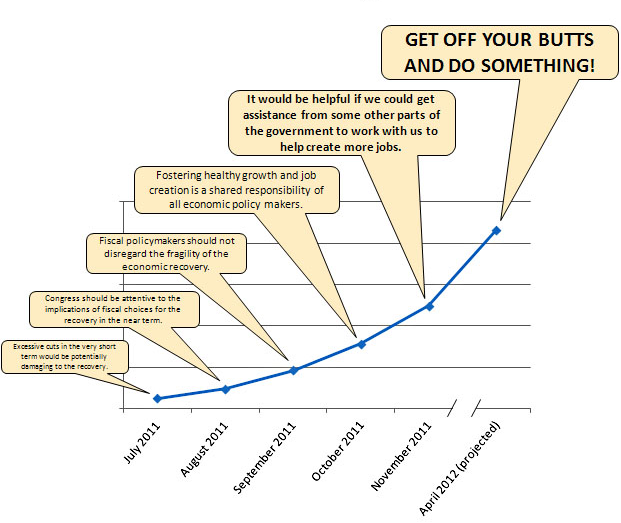

This is a great graphic put together by Kevin Drum, who calls it “The Ben Bernanke Congress-ometer” (go read the original post for context):

Remember: Ben Bernanke was appointed by George W. Bush. Prior to that he headed Bush’s Council of Economic Advisers. For all intents and purposes, he’s a Republican. It’s interesting to note that, (1) unlike his fellow Party members, Bernanke’s job prospects do not directly hinge on stagnant growth and incomes (in fact, if you listen to the GOP debates, re-election of the current incumbent might provide Bernanke with more job security), and (2) unlike most of his fellow Party members, Bernanke seems not to have abandoned, sometime around January 2009 (a date whose significance escapes me for the moment), the belief that fiscal policy can stimulate growth.

Comments

Michael Stephens |

[The following is the text of Senior Scholar Randall Wray’s presentation, delivered October 28, 2011, at the annual conference of the Research Network Macroeconomics and Macroeconomic Policies (IMK) in Berlin. This year’s conference was titled “From crisis to growth? The challenge of imbalances, debt, and limited resources.”]

It is commonplace to link Neoclassical economics to 18th or 19th century physics with its notion of equilibrium, of a pendulum once disturbed eventually coming to rest. Likewise, an economy subjected to an exogenous shock seeks equilibrium through the stabilizing market forces unleashed by the invisible hand. The metaphor can be applied to virtually every sphere of economics: from micro markets for fish that are traded spot, to macro markets for something called labor, and on to complex financial markets in synthetic CDOs. Guided by invisible hands, supplies balance demands and all markets clear.

Armed with metaphors from physics, the economist has no problem at all extending the analysis across international borders to traded commodities, to what are euphemistically called capital flows, and on to currencies, themselves. Certainly there is a price, somewhere, someplace, somehow, that will balance supply and demand—for the stuff we can drop on our feet to break a toe, and on to the mental and physical efforts of our brethren, and finally to notional derivatives that occupy neither time nor space. It all must balance, and if it does not, invisible but powerful forces will accomplish the inevitable.

The orthodox economist is sure that if we just get the government out of the way, the market will do the dirty work. Balance. The market will restore it and all will be right with the world. The heterodox economist? Well, she is less sure. The market might not work. It needs a bit of coaxing. Imbalances can persist. Market forces can be rather impotent. The visible hand of government can hasten the move to balance. continue reading…

Comments

Michael Stephens | November 2, 2011

In the LA Times today, Dimitri Papadimitriou writes about the very real danger of seeing the end of economic union in Europe; a union Papadimitriou insists is ultimately worth saving.

He quickly sketches out what a serious first step toward a solution might look like (rather than this patchwork of half-measures that is sure to be torn apart). The latest set of deals don’t look like they will provide the “breathing room” they’re intended to create. What’s needed, Papadimitriou suggests, is for the European Central Bank to step forward with a bond-buying program; something that would perform a function similar to that of the US TARP program.

But calming volatility, providing real breathing room, is just the first step. The next steps in the eurozone triage ultimately need to include serious efforts to tackle the underlying growth problem in Greece:

Greece lacks both an industrial base and the widespread availability of technology. It simply can’t be productive enough to compete with neighbors such as Germany, France or the Netherlands. It’s in deep recession and doesn’t have the resources to grow out of it, even with an easing of its still-enormous debt level.

Most of the austerity measures and reforms in place — and calls to continue or increase them — won’t work. Raising taxes in a society distinguished by flagrant tax evasion has only boosted the shadow economy …

Read the entire op-ed here.

Comments

Michael Stephens |

C. J. Polychroniou delivers his verdict on the recent eurozone “haircut” deal for Greece (that already looks likely to fall apart given yesterday’s news that Papandreou will submit the plan to a sure-to-be-defeated referendum). In this new one-pager, he highlights a number of elements that make the deal destined for failure—even if the referendum were to succeed. The most glaring flaw, says Polychroniou, is the absence of any credible plan for growth (and as the leaked “troika” document reveals, even some policymakers in the eurozone are coming to admit that “austerity!” does not constitute such a plan):

More fundamentally, a 50 percent haircut alone will not solve the Greek debt problem. When all is said and done, neither recapitalizing European banks nor turbo-charging the EFSF (especially with dubious schemes) can credibly resolve the eurozone crisis without also enacting policies to promote long-term growth. And at this stage, the only viable and immediate solution to reviving the economies of Greece and the other European member-states is through public spending and quantitative easing. But these are policies that are precluded by Germany’s incorrigibly stubborn disposition toward expansionary fiscal consolidation.

Read the one-pager here.

Comments

Gennaro Zezza | November 1, 2011

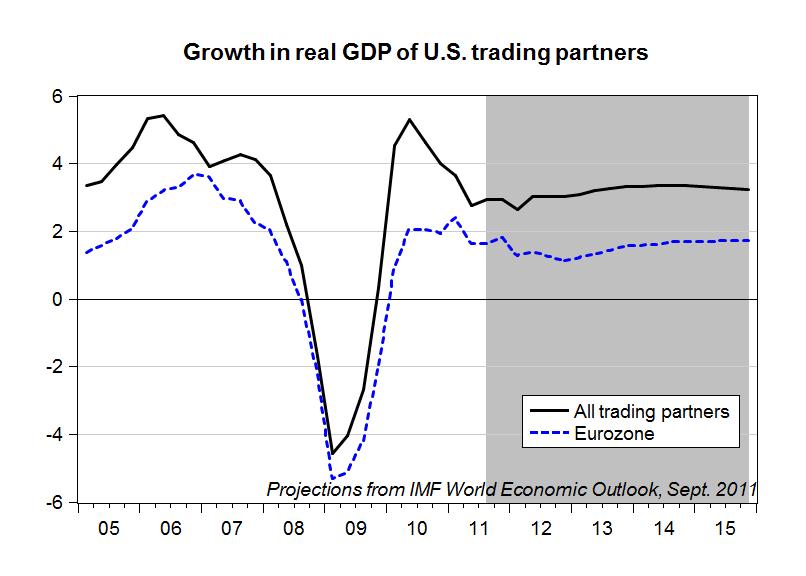

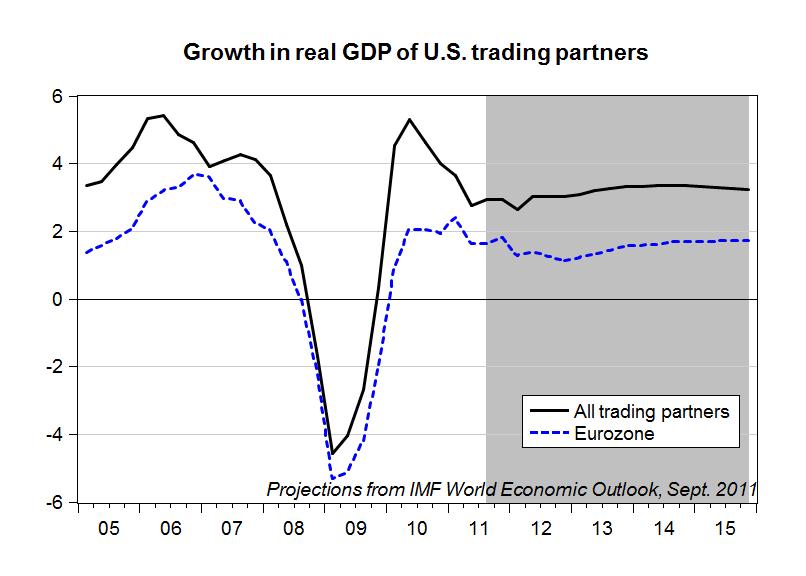

This post provides our latest update of the quarterly figures for the real and nominal GDP of U.S. trading partners (1970q1-2016q4), which were presented a few years ago in a Levy Institute working paper and have now been updated to the second quarter of 2011, with predictions up to 2016 based on the latest IMF World Economic Outlook.

The database has been requested over the years by other researchers, so we decided to put it up on our web site. It is, and will be, available here: http://www.levyinstitute.org/pubs/gdp_ustp.xls

Our index for the annual growth rate in the real GDP of U.S. trading partners, reproduced above, now shows that no boost in U.S. exports from accelerating growth in the rest of the world can be expected. More specifically, according to the IMF the eurozone will not contribute much to global growth, and if fiscal consolidation in Southern European countries will indeed be implemented, we expect a further slowdown in the area. Given that the eurozone accounts for roughly 16 percent of U.S. exports, the impact on the U.S. economy of a European slowdown, through trade, will not be dramatic — certainly not as dramatic as the potential negative impact on financial wealth if the eurozone sovereign debt crisis spirals out of control.

Comments

Michael Stephens | October 31, 2011

At Eurointelligence, Rob Parenteau digs into a recently-leaked “Troika” (the IMF, European Central Bank, and European Commission) document that discusses the outlines of a Greek debt restructuring deal. Among the revelations Parenteau extracts from the document is evidence of a growing willingness to concede that fiscal consolidation is not expansionary. As Parenteau comments:

In 2009 and 2010, citizens across the eurozone were sold large, multi-year tax hikes and government spending cuts on the idea that [expansionary fiscal consolidations] are commonplace and achievable, and besides, balanced fiscal budgets are a sign of prudence and moral purity. In fact, a closer inspection of history suggests fiscal consolidation will tend to be expansionary only under fairly special conditions, namely when accompanied by a) a fall in the exchange rate that improves the contribution of foreign trade to economic growth, and b) a fall in interest rate levels that improves interest rate sensitive spending by households and firms.

Notice that neither of these special conditions are automatic, and neither of them have been present in the eurozone of late.

Read the whole article, including a link to the leaked document, here.

Comments

Michael Stephens | October 28, 2011

Sign up here to get the latest updates on new publications at the Levy Economics Institute, including Institute news, featured scholars, and media appearances, sent directly to your inbox.

Comments

L. Randall Wray | October 27, 2011

[The following is the text of my keynote presentation delivered October 20th at “The Capitalist Mode of Power: Past, Present, Future,” a conference that took place at York University in Toronto.]

Back in 1997 I was finishing up my book titled Understanding Modern Money and I sent the manuscript to Robert Heilbroner to see if he’d write a blurb for the jacket. He called me immediately to tell me he could not do it. As nicely as he could he said (in the most soothing voice), “Your book is about money—the most terrifying topic there is. And this book is going to scare the hell out of everybody.”

Here we are a decade and a half later and I’m still scaring them. Why? Because nobody wants the truth about money. They want comforting fictions, fantasies, bedtime stories. As Jack Nicholson put it: “They can’t handle the truth.”

To be sure, on the left the story is about the evil Fed and bankers and conspiracies against the poor; on the right it is the evil Fed and Congress and conspiracies against the rich. The one thing they seem to be coalescing around is the need for a return to sound money—and I note that Ron Paul and Denis Kucinich are inching toward consensus on that—although they don’t necessarily agree on what is sound.

What I want to do today is to argue that both the left and the right as well as economists and policymakers across the political spectrum fail to recognize that money is a public monopoly. continue reading…

Comments

Michael Stephens |

Ryan Avent digs into the latest GDP numbers at Free Exchange and lays out a set of facts that ought to be drilled into the heads of the public and every opinion-maker: fiscal policy, particularly when you factor in state and local governments, has basically been either null or contractionary for almost two years now.

Federal government spending contributed positively to growth, as an increase in defence spending offset cuts on the non-defence side of the ledger. That positive federal contribution, in turn, offset continued contraction at the state and local government level. All told, the government contribution to output was essentially nil. Government consumption has contributed positively to growth in just 2 of the last 8 quarters. Non-defence federal government spending has contributed positively to growth in just 1 of the last 5 quarters. Generally speaking, fiscal policy has not been stimulative in nearly two years and has been clearly contractionary for the past four quarters. That’s a remarkable situation to contemplate given the rock bottom rates on Treasuries.

Truly remarkable. Multiplier Effect recently featured a couple of posts pointing to Levy scholars arguing that aggregate demand management and short-term stimulus are inadequate to the challenges we’re facing. It’s important to emphasize, however, that this does not mean the near-term fiscal position is irrelevant. The status quo, for some time now, has not been marked by fiscal stimulus of any kind. This economy needs more demand and the federal government has more than enough fiscal room to provide it; the fact that we may need a lot more than merely short-term stimulus does not detract from this point.

Comments

Michael Stephens | October 26, 2011

James Galbraith, interviewed by Henry Blodget, suggests that more “stimulus,” if this means a program that will run out in a couple of years, is not sufficient. What we need, he insists, is something more like a “strategic plan” for the next 10-15 years, investing in growth and dealing with problems like energy, climate change, and infrastructure (and that laying this groundwork would ultimately shore up private sector confidence). Galbraith is also careful to distinguish between concerns about private and public debt: while private, household debt has been a problem for the US, he argues, the public debt is sustainable and should not be a concern. His closing line is worth repeating: “We’re a big country. We can finance our own reconstruction if we choose to do so.”

Comments

ShareThis

ShareThis