Deficit Lovers?

Here’s a piece from yesterday’s NYTimes by Annie Lowrey: “Warren Mosler, a Deficit Lover With a Following.”

In the piece, Lowrey quotes blogger Mark Thoma as follows:

“They [followers of MMT] deny the fact that the government use of real resources can drive the real interest rate up,” said Mark Thoma, an economics professor and widely followed blogger who teaches at the University of Oregon. After delving into the technical details of modern monetary theory for a few minutes, he paused, then added, “I think it’s just nuts.”

Thoma might have been misquoted, but the “real interest rate” is a compound term, comprised of the nominal interest rate and the rate of inflation. Technically, the real rate is the nominal rate less expected inflation. As we know, the Fed sets the overnight nominal rate. The real rate is then the Fed’s target rate less expected inflation.

Now, it is possible that “government use of real resources” might raise expectations of inflation. That is what gold buggism is all about. So let us say Ron Paul whips up inflationary expectations. What happens to the real rate? Well, we are subtracting a bigger expected inflation number from the Fed’s target rate. So the real rate goes down! Now, Thoma might think the Fed will also react to Ron Paul’s gold buggism and so increase its target rate. How much? Who knows. Is there any guarantee the Fed will raise it more than Ron Paul raises inflation expectations? I see no reason why one would jump to that conclusion. And historically, the ex post real rate does often fall when inflation rises (it even goes massively negative).

That is not proof that it is impossible for the real rate to rise when government uses real resources, but there’s no reason to think the real rate automatically goes up. It depends. On whether inflation expectations increase by less than the Fed raises the nominal rate target.

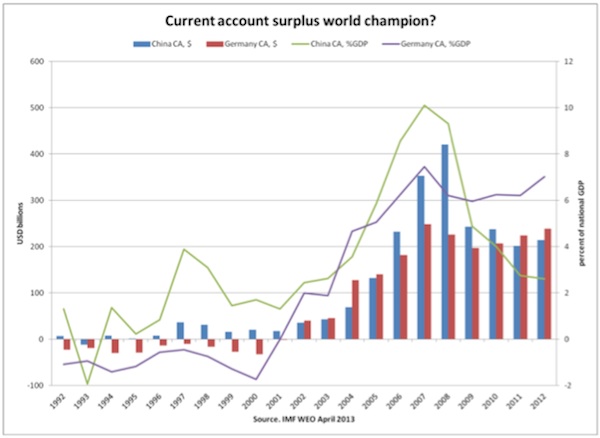

Finally, Warren and “Deficit Owls” are by no means “deficit lovers” – so Lowrey’s title is misleading. There’s a time for deficits, a time for balanced budgets, and even a time for budget surpluses. It all depends on the other two sectors (reminder: Government Balance + Private Domestic Balance + Foreign Balance = 0). A more accurate title would have been: Warren Mosler: Not Afraid of Deficits.

ShareThis

ShareThis