Dimitri Papadimitriou, Gennaro Zezza, and Michalis Nikiforos have put together a stock-flow consistent model for Greece in order to analyze the path of that nation’s struggling economy and assess alternatives to reigning austerity policies. This is a macroeconomic model based on the New Cambridge approach of Wynne Godley and is the same sort of model used for the Levy Institute’s US strategic analysis series.

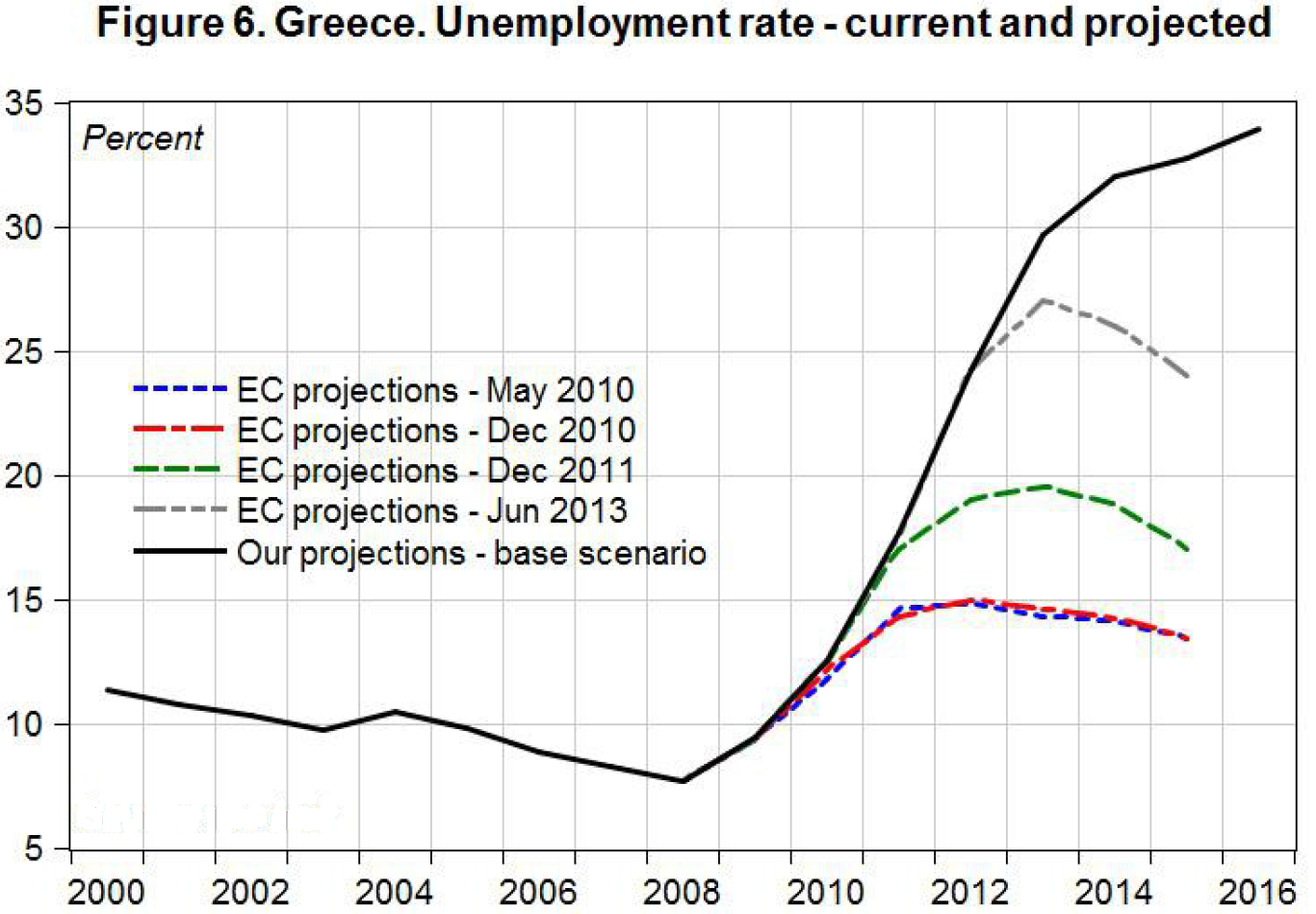

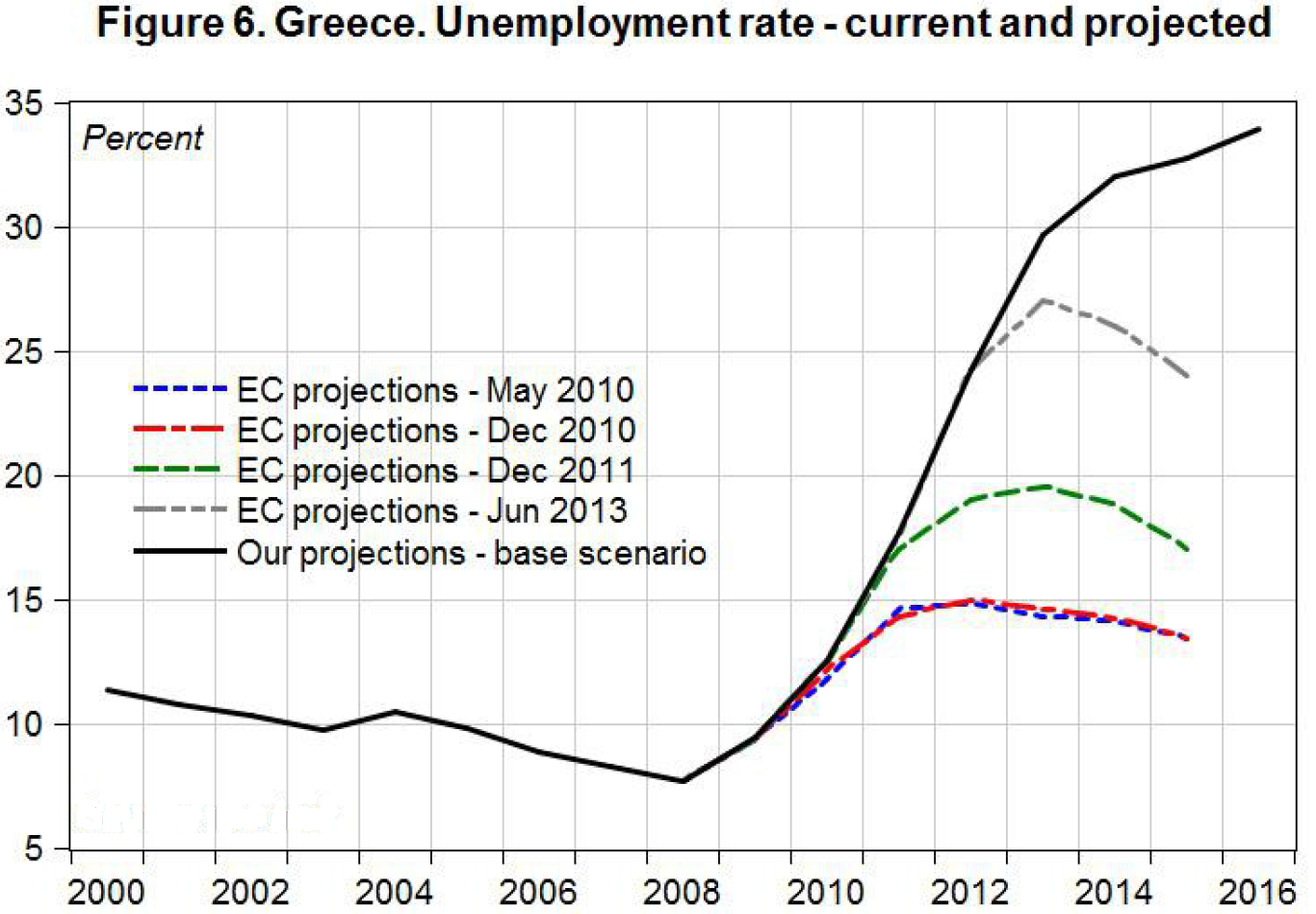

One thing the results of their simulations make clear is that the European Commission (EC) and International Monetary Fund (IMF) have been consistently too optimistic about the Greek economy and the effects of continuing with austerity policies — and still are, even after the IMF’s admission that it had overestimated the benefits of fiscal contraction. Here, for instance, are the EC’s past and current projections for Greek unemployment, compared to the actual results and the Levy Institute’s projections through 2016.

As you’ll notice, the baseline projection generated by the Levy Institute model for Greece (LIMG) shows a rather more dire path for unemployment going forward, compared to the EC’s latest projections. If current policies continue, the unemployment rate could rise from its ruinous 27.4 percent to almost 34 percent by the end of 2016.

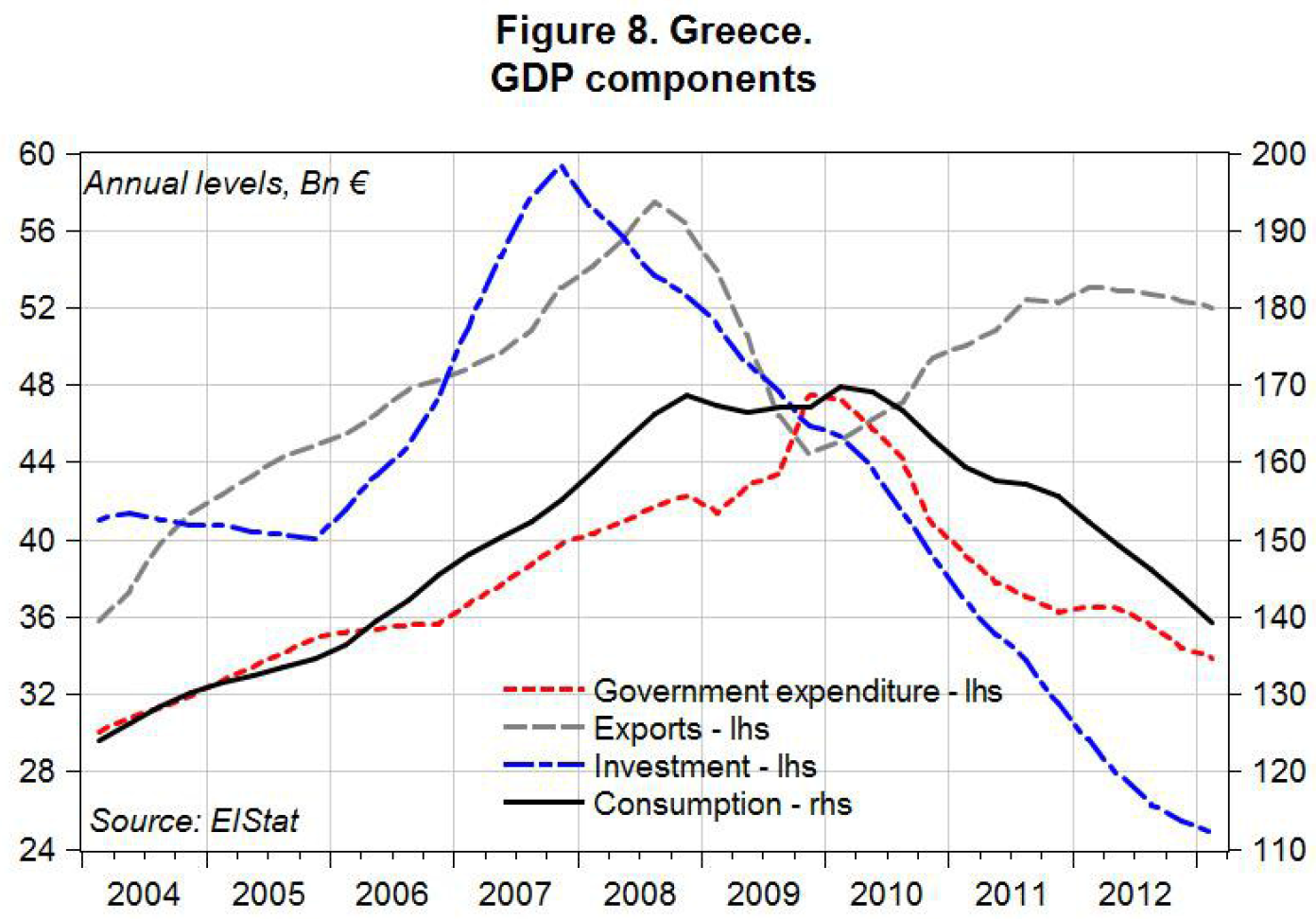

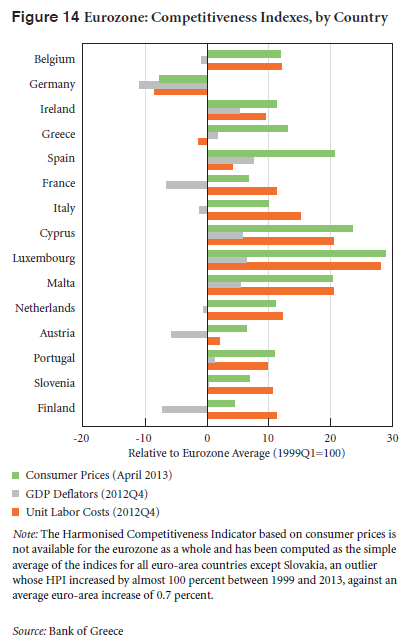

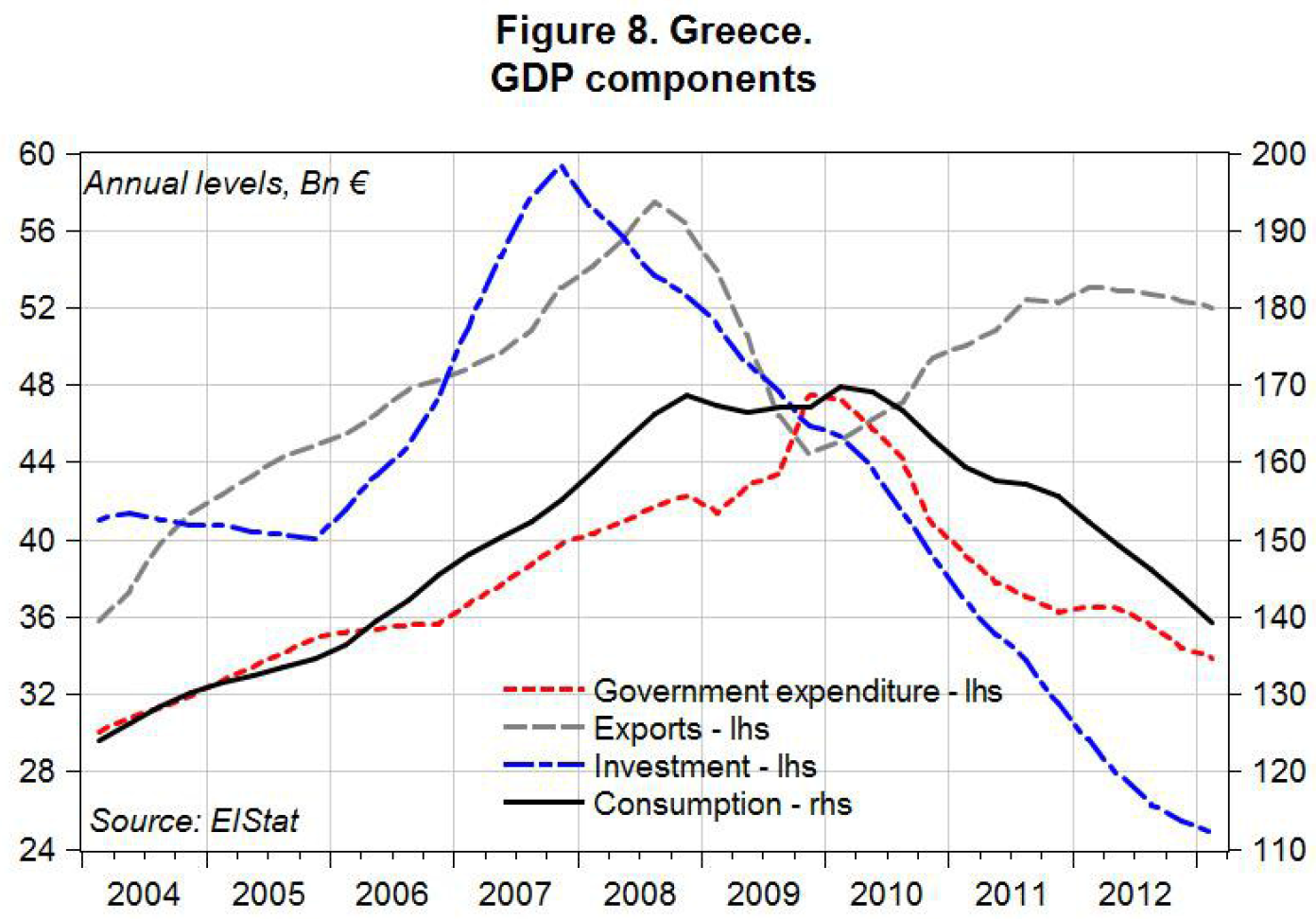

The troika’s (EC/IMF/ECB) “internal devaluation” strategy — based on the idea that forcing a reduction in wages will increase competitiveness and boost export-led growth — isn’t faring well. Cutting wages by government fiat has contributed to a drop in domestic consumption. And as you can see below, while there was an increase in Greek exports that accompanied the onset of fiscal contraction, exports have not risen by nearly enough to compensate for the decrease in the other components of aggregate demand (from their trough, exports grew by almost 8 billion euros; over the same period, government expenditure alone fell by 13 billion euros).

The authors acknowledge that it’s possible exports could grow further, but it’s unlikely that the increase in net exports will be sufficient to make up for plummeting investment, consumption, and government expenditure (and the latest data show that Greek exports were actually declining in the last quarter of 2012). “The implication of our findings,” they conclude, “is that achieving growth in exports through internal devaluation will take a very long time, and furthermore, declining fortunes of the country’s major trading partners do not bode well for [Greece’s] exports.”

The troika’s continued devotion to faulty intellectual doctrines creates serious contradictions in terms of its deficit targets for Greece and its attendant expectations for growth and employment. This new stock-flow model for the Greek economy makes that all the more evident: the authors show that a fiscal stimulus worth around 41 billion euros would be necessary for Greece to reach the troika’s GDP target for the middle of 2016. That would require Greece’s deficit to rise to 12 percent of GDP. Needless to say, that amount — or any amount — of fiscal stimulus isn’t in the troika’s plans.

Papadimitriou, Nikiforos, and Zezza call for a “Marshall plan” for Greece: an investment, funded by the European Investment Bank (EIB), in an expanded public service job creation program — a program that has had impressive results in other countries and, on a smaller scale, in Greece itself.

The strategic analysis for Greece (download an early look at the full report here) is accompanied by a technical report that explains the specification of the model and discusses in more detail how the data were used.

ShareThis

ShareThis