The Vampire Squid of Wall Street Is Hemorrhaging

(cross posted at EconoMonitor)

Government Sachs posted its second quarterly loss since it went public in 1999. No doubt that has sent Washington scrambling to try to plug the leak. (Wouldn’t it be fun to listen in on Timothy Geithner’s incoming phone calls from 200 West Street, NYC, today?)

Lloyd “doing God’s work” Blankfein blamed the “uncertain macroeconomic and market conditions”—conditions created, of course, by Wall Street. And since Wall Street refuses to let Washington do anything to improve those conditions, expect much more hemorrhaging among Wall Street’s finest.

The big banks are toast, as I’ve been saying for quite some time. There is no plausible path to real profits with the economy tanking. Only jobs—millions and millions of them, as well as comprehensive debt relief will stop that.

As I wrote a couple of weeks ago:

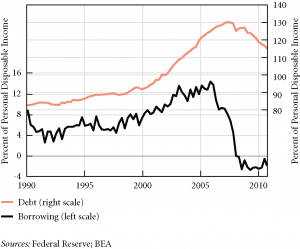

“US and European banks probably are already insolvent. When Greece defaults and the crisis spreads to the periphery that will become more obvious. The smaller US banks are in trouble because of the economic crisis. However, the biggest banks that caused the crisis are still reeling from their mistakes during the run-up to the crisis. They were already insolvent when the GFC hit, and are still insolvent. Policy makers have pursued an “extend and pretend” approach to hide the insolvencies, however, the sorry state of these banks will be exposed when the next crisis begins to spread. It is looking increasingly likely that the opening salvo will come from Europe, although it is certainly possible that it could come … The economy is tanking. Real estate prices are not recovering, indeed, they continue to fall on trend. Few jobs are being created. Defaults and delinquencies are not improving. GDP growth is falling. Household debt as a percent of GDP is only down from 100% to 90%. While declining debt ratios are good, it is still too much to service. Consumer debt fell from $12.5 trillion in 2008 to $11.4 trillion now. Total US debt is about five times GDP and while household borrowing has gone negative, debt loads remain high. Financial institutions are still heavily indebted—mostly to one another. At the level of the economy as a whole, it is still a massive Ponzi scheme—that will collapse sooner or later… No real economic recovery can begin without job growth in the neighborhood of 300,000 new jobs per month and no one is predicting that for years to come.

Isn’t it strange that Wall Street has managed to remain largely unaffected? continue reading…

ShareThis

ShareThis