This article is republished with permission from the author from the Center for Human Rights and the Arts webpage.

Described by The Guardian as “an amplifier of ideas,” Cooking Sections is an art duo established in London in 2013 by Daniel Fernández Pascual and Alon Schwabe. Nour Annan, MA student in the Human Right and the Arts ‘23, caught up with them on the eve of the U.S. premiere of When [Salmon Salmon [Salmon]], as part of the Fisher Center LAB Biennial, Common Ground.

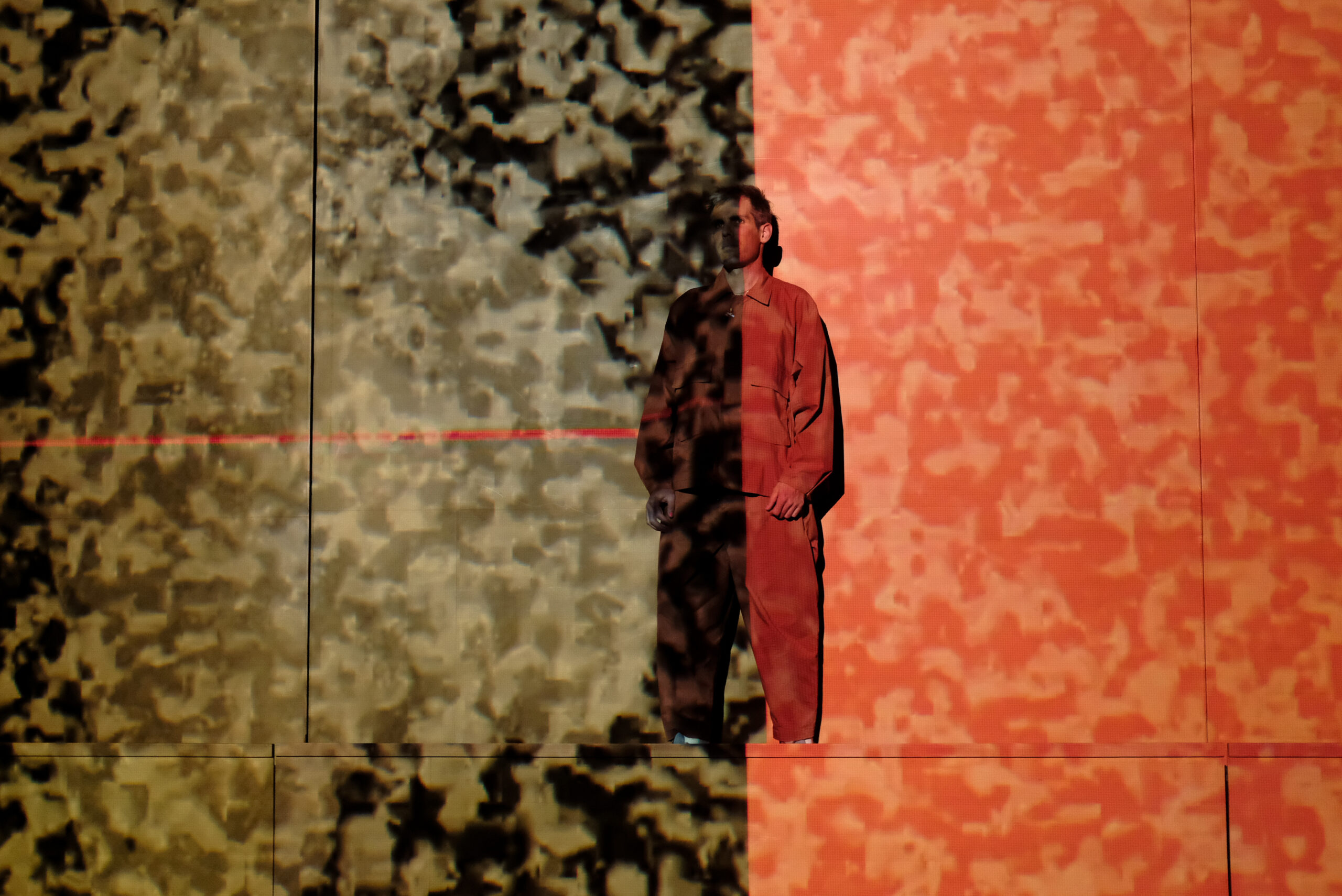

When [Salmon Salmon [Salmon]] is a three-part performance installation. The trilogy explores the impact of food production based on extractive systems that push the environment to the verge of collapse, and each part traces the effects of salmon farms on multiple ecologies. Through performance and installation, the works examine farmed salmon as a constructed animal, one of the most recently-domesticated and industrialized species in history.

Salmon: A Red Herring, is a lecture performance that questions what colors we expect in our ‘natural’ environment. It asks us to examine how our perception of color is changing as we change the planet. Salmon: Traces of Escapees, is an immersive video installation that explores the environmental impact of salmon farms, which can be traced far beyond the circumference of open-net pens, and everything that escapes through them. And, Salmon: Feed Chains, is a performative installation that subjects the audience to the automated feeding mechanism of the salmon farm. The piece revolves around the eco-systems that are transformed into feed, the landscapes that are fed to farmed fish and the pellets that are consumed by salmon in their feedlots.

Nour Annan (NA): Congratulations on your North American debut of the show!

Cooking Sections (CS): Thank you. We’re really excited.

NA: There have been many iterations of your salmon project over the past few years. How long have you been working on this project specifically?

CS: We’ve been working on the salmon project since 2016, when we were at the Isle of Skye in Scotland, but it was the Tate Britain commission in 2020 that started this installation form of the work.

NA: The performance-installation showing at The Fisher Center, When [Salmon Salmon [Salmon]], is made up of three parts. We’re seeing Salmon: A Red Herring (Part 1), Salmon: Traces of Escapees (Part 2), and Salmon: Feed Chains (Part 3). Have you shown all three parts together before?

CS: Yes, just now actually, we showed them for the first time at Bonniers Konsthall in Stockholm, Sweden. When we knew we wanted to complete the trilogy, we thought it would be great to bring everything here, and co-produce the last chapter between Bonniers Konsthall and The Fisher Center. It was a great addition, it really brings all the parts together.

NA: Can you tell me more about the beginning of the salmon project? How did you come to work on salmon?

CS: It all started when we were invited to work in the Isle of Skye, an island along the northwest coast of Scotland. The first time that we visited Skye, we were still trying to figure out what would make sense for us to do there, and we started talking to different people in the area. One of our first conversations there was with a group of people who have been fighting salmon farms for a long time. They mentioned this story that we had thought was an urban myth, about a house sparrow that had turned pink after eating the feed pellets from the salmon farm. Because the feed pellets contain this synthetic pigment, the color was absorbed and released in the bird’s feathers. That story really captivated us. We almost couldn’t believe it. A little while later, the BBC captured those birds on camera in different places. So we started thinking about all these different animals and colors, and how these colors are flowing through different bodies. That led to this installation format based on the work that we’ve been doing in Skye to divest the island away from salmon farming; through the lens of color, with these new aesthetics that surround us, we try to read all these colors as part of the climate emergency. So for us, we see these salmon-colored birds as a red flag, a signal that something is wrong. And we’d like to think about how to develop new ways of seeing in the climate crisis.

NA: You mentioned how this installation format is only part of the work you had been doing in the Isle of Skye. How does your artistic practice feed into the larger work that you’re doing on the ground in affected areas?

CS: We think a lot about food systems and transformations of food systems in our work. How we can develop more equitable and just infrastructures, whether it’s food infrastructures, land infrastructures, or different societal infrastructures. In that way, this project tried to address some of these questions and it forced us to think of ways to actually change them. Some of these things are quite mediated in a way, like the removal of salmon from the menus of 22 museums all across the UK, and now Bard College has removed farmed salmon off its menus as well. In that way, we provide the framework and people adapt it to their own context, and they can run it on a daily basis that doesn’t depend on a particular event. It’s been quite exciting to hear from some of the restaurants in Skye, about visitors who come in and ask why they don’t have any farmed salmon, so they get invited into that conversation.

But at the same time, there are a lot of processes, including the ongoing work on the Isle of Skye, that directly works to question how we transform space, how we can work to divest an island from salmon farming, and how do we create common land and bring it back to the control of the people who have lived there for many many generations.

NA: Did you observe any noticeable differences when you were presenting the work in different places, perhaps depending on a geography’s relationship to particular food systems?

CS: To a certain extent, yes. But actually with this work in specific, it’s quite interesting that salmon has become such a ubiquitous kind of fish that is available everywhere, and has been made relatively affordable, at least over the past few years. So in the places that we have spoken about it so far, even places like here in the Hudson Valley, where salmon is not farmed locally, it is still very popular. So if you go to restaurants pretty much anywhere in the area, they have salmon on the menu, and that salmon is farmed. In a way this also shows the extent of the problem, how these things manage to circulate and arrive at so many places that are very distinct from each other culturally and geographically. So when the work manages to bring all of these geographies together, it’s reflective of how these places that seem very distant from each other are all held together by these broken food systems.

NA: There’s a very strong focus on spatiality and landscape throughout your work. Can you talk more about how spatiality plays into this critical examination of food?

CS: For us, from the beginning, space played a big role in the way we situate ourselves but also in observing the bodies around us. And part of the preoccupation with our practice was also to understand the different systems that organize that space through the lens of food. So, the construction of landscapes, all these political powers, economic regimes, all these different layers that organize not only space but also how different bodies, human and non-human, inhabit that space. So we place a lot of emphasis or attention on space in order to further understand how those different spaces change overtime.

NA: Speaking of beginnings, I’m curious, did you start examining food from the very start, or did you find yourself gravitating towards that through your collaborations?

CS: Our conversation started around food, mainly around a project we did with a community of around 400 Iñupiaq people on the northwest coast of Alaska, in Kivalina. There, food was a very important lens to understand how the people living there, in a very particular landscape that many would perhaps see as harsh, but who have lived there and thrived for generations upon generations. So looking at food was really helpful to understand the violence of the settler colonial project, the changing environment, and how the climate crisis was put in action there. There, we started thinking of food and looking at food practices and considering how food can be a prism through which to understand the world. In considering the histories of violence and dispossession, we also wonder how we can use food as a tool to think about alternative futures. That’s kind of how it started, and the practice has been revolving around those questions ever since. So it’s not that we started looking into one thing and it evolved into this, food systems have been at the core of our work from the beginning.

NA: And what is it like for you guys working together as collaborators? Did it start off as an occasional project and then developed into Cooking Sections?

CS: No. We started collaborating and it’s been a very intense and close partnership from the beginning. And I guess the practice is based on this kind of partnership. It’s personal, it’s artistic, it’s a work partnership, it has many layers.

NA: While these projects take on different forms, they remain quite symbiotic, always in conversation with one another. I’m really interested in The Empire Remains Shop, which really stands out in its somewhat unconventional approach. What was it like to run this “shop”?

CS: The Empire Remains Shop project started in 2013. One aspect of that project is actually one of our earliest collaborations. It started perhaps as a reaction to us both living in London without being from London. Again, we were trying to understand the systems that surrounded us, and the legacies of those systems. Then we came across these empire marketing boards from the 1920s that were part of a governmental propaganda machine to market products from the colonies and overseas territories back then, trying to indoctrinate people on how to consume products from empire. Luckily, these shops never opened. But we decided to open a version of that as a performative space and to invite people, over 40 contributors, to respond to those legacies of empire today. Again, working through the lens of food, and in many different contexts. So it wasn’t a comprehensive methodology in any way, it was more of the activation of a space to think about these questions for three months, and it happened to be between the Brexit vote and Trump’s election. So it was a space for discussions, exchange, conversations, sculpture, performance, and meals. We found this space, invited people to contribute, and then those people invited their colleagues as well, so it kind of grew over three months. We realized then how hard it is to manage an artist-run space. But it was all very exciting.

NA: How did these different works evolve into the long-term site-responsive CLIMAVORE project?

CS: CLIMAVORE kind of grew out of The Empire Remains Shop and the work that we were doing in the Isle of Skye at the same time. We were doing all this research on food and food systems, and we were thinking: Okay, there’s a climate crisis, that’s very clear, but also the way that humans are eating is changing the climate. That was the beginning of the idea of CLIMAVORE, this platform that we initiated to engage with this new season of the climate crisis. So we’re asking, how do we eat in a period of drought? How do we eat in a period of ocean pollution? How do we eat in a period of floods, and so on? And it really makes an argument that we cannot continue eating the way that we are eating. That this idea of seasonality, as we conceive of it in the global North, is completely non-existent. CLIMAVORE then becomes a sort of methodology, but also a series of projects that exist all over the world, which includes interventions into different institutions by changing the food that they serve to the people that inhabit these spaces.

NA: You mentioned earlier how living in London without being from there influenced your understanding of the systems in place. How do you feel that kind of outsider eye has informed your work, whether in London or elsewhere?

CS: It depends, but of course as a foreigner, you also notice a lot of things that are sort of being taken for granted. And I think this is also part of the way we practice; and like many people, the fact that you get invited into spaces, this is part of your agency, to be able to illuminate something about the space by having a set of eyes that aren’t so embedded into those surroundings, to ask, oh why is this happening in this way? Why does everyone think that this is that? And this is very much part of the work we’re all doing in a way. Sure, it’s true for us living in London, but it’s also true for us working in all of these different places, and also when coming here. In a way, you have the opportunity to learn from great things that are already happening and think of how you can work with them or enhance or complement them.

NA: How would you respond to the art world definitions of your work, when people ask if it is art or research or activism or knowledge production? Do you feel like you have to play into those distinctions in certain cases?

CS: We try not to label ourselves, but people come up with many terms. Which is fine, we’re not necessarily for or against any of them. For us, what is important is to operate very fluidly in the different terrains, because sometimes it’s important that you are seen as a certain character, other times it’s a different character. From engaging with certain interlocutors, to producing credible knowledge, to fundraising, to bringing new partners on board, we need to wear many hats for the different missions that we have.

When [Salmon Salmon [Salmon]] showed at The Fisher Center October 13–16, 2022, as part of Common Ground: A Festival on the Politics of Land and Food, curated by Tania El Khoury and Gideon Lester.

Reply